case 1

11 y/o girl, presented with acnes over face, chest and upper back, more hair growth over lower legs, with no M.C.

testosterone 155.7 (高)

progesterone < 0.14

estradiol 58.99 (高)

LH 3.48 (高)

FSH 4.94

normal thyroid and cortisol

PCOS

-the most common form of

chronic anovulation a/w

androgen excess;

-

5% to 10% of reproductive-age women.

Dx: (women with chronic anovulation and androgen excess)

-先排除 other hyperandrogenic d/o

-nonclassic adrenal hyperplasia,

-androgen-secreting tumors, (腎上腺,卵巢)

-hyperprolactinemia)

Criteria for the Definition of PCOS

NIH Statement (1990)

To include all of the following:

1. Hyperandrogenism and/or hyperandrogenemia

2. Oligo-ovulation

3. Exclusion of related disorders*

ESHRE/ASRM Statement (Rotterdam, 2003)

To include two of the following, in addition to exclusion of related

disorders

*:

1. Oligo-ovulation or anovulation (e.g., amenorrhea, irregular uterine

bleeding)

2. Clinical and/or biochemical signs of hyperandrogenism (e.g., hirsutism,

elevated serum total or free testosterone)

3. Polycystic ovaries (by ultrasonography)

AES Suggested Criteria for the Diagnosis of PCOS (2006)

To include all of the following:

1. Hyperandrogenism: hirsutism and/or hyperandrogenemia

2. Ovarian dysfunction: oligo-anovulation and/or polycystic ovaries

3. Exclusion of other androgen excess or related disorders*

*Including but not limited to 21-hydroxylase-deficient nonclassic adrenal hyperplasia, thyroid dysfunction, hyperprolactinemia, neoplastic androgen secretion, drug-induced androgen excess, the syndromes of severe insulin resistance, Cushing’s syndrome, and glucocorticoid resistance.

NIH, National Institutes of Health;

ESHRE, European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology;

ASRM, American Society for Reproductive Medicine;

AES, Androgen Excess Society.

PCOS 病生理

-A

deficient in vivo response of the ovarian follicle to physiologic quantities of FSH, possibly because of an impaired interaction between signaling pathways associated with FSH and insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) or insulin, may be an important defect responsible for anovulation in PCOS.

-

insulin resistance associated with increased circulating and tissue levels of insulin and bioavailable estradiol (E2 ), testosterone (T), and IGF1 gives rise to abnormal hormone production in a number of tissues.

-Oversecretion of LH and decreased output of FSH by the pituitary, decreased production of sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG) and IGF-binding protein 1 (IGFBP-1) in the liver, increased adrenal secretion of dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), and increased ovarian secretion of androstenedione (A) all contribute to the feed-forward cycle that maintains anovulation and androgen excess in PCOS.

-Excessive amounts of E2 and T arise primarily from the conversion of A in peripheral and target tissues.

-T is converted to the potent steroids estradiol or DHT (dihydrotestosterone).

-Reductive 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17β-HSD) enzyme activity may be conferred by protein products of several genes with overlapping functions;

-5α-reductase (5α-red) is encoded by at least two genes, and aromatase is encoded by a single gene.

GnRh, gonadotropin-releasing hormone.

Extraovarian conversion of androstenedione to androgen and estrogen

-Androstenedione of adrenal or ovarian origin, or both, acts as a dual precursor for androgen and estrogen.

-Approximately 5% of circulating androstenedione is converted to circulating testosterone, and approximately 1.3% of circulating androstenedione is converted to circulating estrone in

peripheral tissues.

-Testosterone and estrone are further converted to bio-logically potent steroids, dihydrotestosterone and estradiol, in peripheral and target tissues.

-Biologically active amounts of estradiol in serum are measured in picograms per milliliter (pg/ml, or pmol/l), whereas biologically active levels of testosterone in serum are measured in nanograms per milliliter (ng/ml, or nmol/l).

-the 1.3% conversion of normal quantities of androstenedione to estrone may have a critical biologic impact in settings such as postmeno-pausal endometrial or breast cancer.

-significant androgen excess is observed in conditions with abnormally increased androstenedione formation (e.g., polycystic ovary syndrome).

DDx:

-Idiopathic

hirsutism

-Hyper

prolactinemia,

hypothyroidism.

-Nonclassic

adrenal hyperplasia,

Adrenal tumors,

Cushing’s syndrome,

Glucocorticoid resistance.

-

Ovarian tumors

-Other rare causes of androgen excess

CHAR:

-infertility,

-irregular uterine bleeding, and

-

↑ pregnancy loss.

-

endometrium biopsy, because long-term unopposed estrogen stimulation leaves these patients at

↑risk for

endometrial cancer.

-

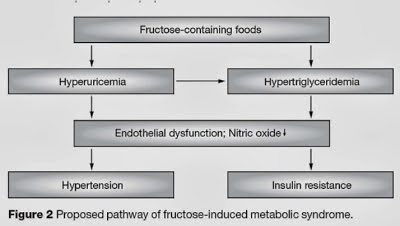

↑metabolic and CV risk factors.

-->linked to

insulin resistance and

-->are compounded by the common occurrence of

obesity, (although insulin resistance also occurs in nonobese women with PCOS.)

-considered to be a heterogeneous disorder with multifactorial causes.

-

PCOS risk is

-significantly increased with a positive family history of chronic anovulation and androgen excess, and

-may be inherited in a polygenic fashion.

------------------------------------------------------------

Historical Perspective

In their pioneering studies, Stein and Leventhal described

an association between the presence of bilateral polycystic

ovaries and signs of amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, hirsut-

ism, and obesity (Fig. 17-29). 250 At the time, these signs

were strictly adhered to in the diagnosis of what was then

known as Stein-Leventhal syndrome. These investigators also

reported the results of bilateral wedge resection of the

ovaries, in which at least half of each ovary was removed

as a therapy for PCOS. Most of their patients resumed

menses and achieved pregnancy after ovarian wedge resec-

tion. They postulated that removal of the thickened capsule

of the ovary would restore normal ovulation by allowing

the follicles to reach the surface of the ovary. The exact

mechanism responsible for the therapeutic effect of removal

or destruction of part of the ovarian tissue is still not well

understood.

On the basis of Stein and Leventhal’s work, a primary

ovarian defect was inferred, and the disorder was com-

monly referred to as polycystic ovarian disease. Subsequent

clinical, morphologic, hormonal, and metabolic studies

uncovered multiple underlying pathologies, and the term

polycystic ovary syndrome was introduced to reflect the het-

erogeneity of this disorder.

One of the most significant discoveries regarding the

pathophysiology of PCOS was the demonstration of a

unique form of insulin resistance and associated hyperin-

sulinemia. 142 Burghen and coworkers first reported this

finding in 1980. 251 The presence of insulin resistance in

PCOS has since been confirmed by a number of groups

worldwide. 142

Diagnosis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Laboratory Testing

臨床

-

ovulatory dysfunction (i.e., amenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, or other forms of irregular uterine bleeding) of pubertal onset.

-A clear history of cyclic predictable menses of menarchal onset makes the diagnosis of PCOS unlikely.

-Acquired insulin resistance associated with significant weight gain or an unknown cause may induce the clinical picture of PCOS in a woman with a history of previously normal ovulatory function.

-Hirsutism may develop prepubertally or during adolescence, or it may be absent until

the third decade of life.

-Seborrhea, acne, and alopecia are other common clinical signs of androgen excess.

-In extreme cases of ovarian hyperthecosis (a severe variant of PCOS), clitoromegaly may be observed. Nonetheless, rapid progression of androgenic symptoms and virilization are rare in PCOS.

-Some women may never have signs of androgen excess because of hereditary differences in target tissue sensitivity to androgens. 148

-Infertility related to the anovulation may be the only presenting symptom.

-During the physical examination, it is essential to search for and document signs of androgen excess (hirsutism, virilization, or both), insulin resistance (acanthosis nigricans, Fig. 17-30), and the presence of unopposed estrogen action (well-rugated vagina and stretchable, clear cervical mucus) to support the diagnosis of PCOS.

-None of these signs is specific for PCOS, and each may be associated with

any of the conditions listed in the differential diagnosis of

PCOS (Table 17-5).